by G. Wilford Hathorn

© 2001. All Rights Reserved

After reading my web page some people posed questions about my feelings toward victims, remorse, and taking responsibility for one's actions. Some even asked to hear "my story", therefore I think it time I shed some light on these worthy topics.

I have supported victims survivors for many years. To understand what these people endure I put myself in their place and took an honest look at how I would feel if a loved one, my son for instance, were violently taken away, and what I experienced in this hypothetical scenario was ghastly. Having this new understanding I undertook to always remember victims. In the past I have written of my support for victims, but because I had no web page then not many people read these writings. Additionally, when I was Chairman of the Lamp of Hope Project it was I who convinced my fellow Board Members, four other death row inmates, to make concern for victims a prominent part of our mission statement; this statement still exists, and I dare say one will not find many other prisoner's rights organizations who in their literature mention a desire to help victims heal. From my view it is hypocritical to ask for mercy from the public if one isn't willing to extend mercy, via acknowledgment and understanding of another's suffering, to those he has hurt.

Often when one is executed he from the gurney addresses the survivors of his victim and apologizes for the pain he has caused them, and this is well, but this seems like an eleventh-hour gambit to pave one's way into Heaven. Appellate attorneys may cringe at my words, but I believe if one is truly remorseful he should express this sentiment at the earliest possible date, rather than at the last minute. I understand one's reasons for not doing so, such as an apology being an admission of guilt and the utterance thereof possibly counting against someone in his appeal, but -- and I speak for myself here, no one else -- one must decide whether he wishes to cleanse his soul and do what he can to help those he hurt or maintain a facade until he is strapped to the killing table and then speak words that due to belatedness lack sincerity. Toward this end I have contacted or attempted to contact all those who were hurt by the ripple effect of my past actions. To the ones with whom contact was successful I acknowledged their loss and pain, apologized for causing same, and let them know that daily I am dashed on the rocks of sorrow for being so blind as to not realize what consequences my actions would create. Some accepted my overtures and are now on the road to healing, others rebuffed them and are mired in the bog of anger. But the effort was made and I am wiser for having made it. I am not a saint, just a person who via self-introspection and contemplation has chosen to grow rather than stultify and view the world and those in it with resentment.

To share a bit about myself and the circumstances that brought me to death row, the first thing I'll say is that I am not a career criminal; this is my first trip to prison. I was raised in a small East Texas county and grew up in the middle of the woods, so I am country to the bone. The school from which I graduated boasted 125 students grades kindergarten-12, and vocational agriculture was an important part of every boy's life so that in the event he didn't finish school he could work at farming, ranching, or perhaps become a logger. I was a farm boy who worked summers in the hay fields and cleaned septic tanks to supplement my income, which came in handy during the winter when there was no hay to haul. I liked to fish and my mouth still waters when I recall eating catfish and hushpuppies with sides of fresh corn and purple hull peas, with homemade ice cream for dessert. Wildlife was so plentiful that it was not uncommon to see deer tracks in the yard on my way to the school bus stop in the mornings, and a family of flying squirrels inhabiting a rotted old tree near our house.

But beyond the beauties of this pastoral setting was the disease of child abuse, to which I was subjected throughout my formative years and which caused me to become introverted and addicted to long, almost spiritual walks through the woods, which were a citadel of safety and solitude, a haven from the terrors of home. This abuse resulted in a rage-filled backlash that bought my ticket to the row. And no, I did not take my anger out on some stranger on the street. People say, "Why didn't you tell anyone of the abuse and get help?" Keep in mind the setting: East Texas, where pride and toughness define a man and any complaint is viewed as weakness. At least that's how I perceived it then: There may have been people to whom I could turn for help, but if so I did not know who they were. Then there were the feelings of shame I did not wish to reveal, plus no child wishes to get his parents into trouble -- he's forever under the illusion that things will change and the family will live in peace, love, and harmony. And there was the fear of what would happen if I asked someone for help and their efforts to remedy the situation failed; retaliation for having told was something about which I was very concerned.

But the sadder part of this story is that people in my community did know what was happening, but for reasons that escape me never tried to intervene, nor did they come forward at my trial to tell what they know. There is a strong predilection in this part of the state toward minding one's own business, so maybe this is why no one spoke up, I don't know. There have been suggestions that law enforcement intimidation played a part, but again I don't know. After nearly fourteen years on the row I had begun to question whether I had imagined the abuse, as no one but me would acknowledge it, then out of the blue I received a letter from a guy with whom I went to school. We began a correspondence and he indicated that he knew of the abuse, so one day I, unable to take not knowing any longer, asked if other people knew and if so why nothing had ever been said. He responded: "I think a lot of people knew. Even the school staff had their own suspicions. They never said anything around you ... You needed help but at the same time you didn't want anyone to know. So if everyone was quiet the problem would just go away.”

To this day these people have remained silent, so I asked him about that, too. He said: "Why no one has ever said anything, I don't really know. I would guess that maybe they were ashamed they had not spoken sooner (Before the crime) and if they don't now they will never have to.”

Because I am on death row and write about my experiences some people ask where is my concern for victims, yet when I was a victim as a boy in East Texas no one said a word, and still haven't, so this apathy toward those who have suffered is endemic to our society. It is precisely because of the aloof attitude I've experienced regarding what people knew of my early life and the recognition of the pain I've caused others that I support victims and their survivors in their quest for solace, understanding, respect, and healing.

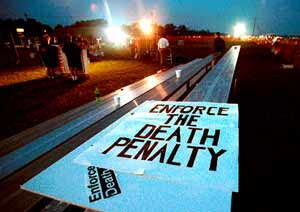

I should, however, point out that while there are those who are sincere in this quest for healing, there are others who use their survivor status as a conduit for hatred and death. These people, whom I'll call death supporters, are quick to refer to the pain of survivors, but by demanding the death of a killer inoculate themselves against the pleas for mercy from other survivors, the mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, sons, and daughters of the condemned. Some death supporters have stated that it is because they cherish life that they support the death penalty, but this position is nonsensical for many reasons, the most remarkable being that they endorse an act that will cause others to experience the same pain and sense of loss that they have felt. As a survivor of child abuse I pray no one else is abused, a survivor of rape wouldn't wish anyone else raped, and a person who has been shot wouldn't wish anyone else shot. Yet the death supporters have no compunction about allowing someone else to taste the bitter pill of loss by death, which exacerbates the phenomena because executions are preventable; we can't bring back those who have fallen to violence, but we can ensure that another family is not in our name robbed of a loved one, regardless of how much we hate the person they love. When asked about the family members of the condemned the death supporters say, “We sympathize with their pain, BUT…." All platitudes in favor of taking life fail to withstand reasoned, moral scrutiny, because when we allow the killing of a person rather than protect his family from the fate we ourselves have suffered we leave in the road an obstacle it is our responsibility, by virtue of our beforehand experience, to remove.

When rage and revenge are the barometers by which people gauge what remedies to promote, the cycle of death perpetuates: first the victim, then the condemned, then the conscience of young people who are taught by their role models that in some cases it is okay to kill. Isn't this what the school massacres in recent years boiled down to, offended, isolated, helpless, and hopeless children taking up arms to render unilateral “justice” against those whom they blamed for their own empty feelings? It is noteworthy that the push for harsher punishments, particularly more and speedier executions, reached a fever pitch (That continued until the 2000 presidential campaign finally gave Americans reason to pause) in the eighties, then the school killings occurred in the nineties. Coincidence? Or had the young assassins listened when people by implication said: “Somebody you don't like? Waste 'em!” This is the message inherent in capital punishment and the children must be hearing it, for at no other time in history have school massacres been a problem.

Texas kills more of its people than any other state, more than some countries, yet despite this and other frontier-style solutions like allowing its citizens to carry concealed guns, it has one of the highest murder rates in the nation. The death penalty is a toilet down which the government may flush its undesirables: The poor, the retarded, the insane, and disenfranchised. For crimes punishment is warranted and expected, but rapists are not raped, arsonists are not incinerated, and assaulters are not beaten, so why kill killers? The logic for it is not there, while the logic opposed abounds. As for victims and their survivors, I will continue to support and pray for them.

T H E E N D